SITE GUIDE

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

DC

New Jersey

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

Review

Review

Permanent Collection

by Rich See

|

What's a few less paintings of naked white women? ---Kanika Weaver |

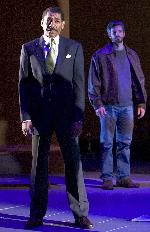

T. Alexander and T. M. Hammond

(Photo: Richard Anderson) |

Written by Thomas Gibbons and originally part of Centerstage's 2003-2004 "First Look" play reading series, Permanent Collection tells the story of a little known art foundation whose autocratic founder, Alfred Morris, has passed away and bequeathed controlling interest of the foundation to Haywood, a historically black university. That Alfred Morris was white and his foundation is located in a white suburban neighborhood factor into the play's proceedings. That Mr. Morris was an anti-art establishment visionary, who snubbed the art world and its -- in his view -- limiting vision of art's generational and geographical scope, also factors into the play's conflict.

Within the play Gibbons sets up certain parameters that are structured by Alfred Morris' will. The foundation must remain in its present location, no paintings may be moved and no art pieces may be added to the exhibits. In fact, no changes of any kind are to be made to the collection which houses Picasso, Renoir, Cézanne, and Matisse, along with a distinctive selection of African art. Since the tyrannical Morris has died, no changes have been made. His vision and views have been carried out to the letter. However, when Sterling North, the foundation's first African American executive director, arrives, change can be felt in the air. North, who has a corporate background and no formal art training, first reassigns Ella, the foundation's long-time executive assistant, so he can bring on Kanika Weaver, a free thinking young woman with an educational background who worked for him in his previous position. Next Sterling brings eight pieces of African Art out of the foundation's vast storage archives and writes a memo to the Board asking permission to display the pieces within the collection, which of course is in direct conflict with Alfred Morris' will.

Enter Paul Barrow, the institution's (white) education director, who has been leading the foundation while the search for an executive director progressed. Paul, who has been passed up for the position, admits to making the foundation the core of his very existence. The only job he has ever held, Paul worked directly with Alfred Morris and lives near by. He is a Morris disciple and derives great satisfaction from simply being around the art hanging on the walls. When he discovers that Sterling is trying to dismantle aspects of the Morris will, Barrow immediately takes steps to try and circumvent what he feels is a disrespect to a great man's vision. And this is when the issue of race enters into the discussion...

Paul foolishly speaks to a journalist about Sterling's impending memo, Sterling responds to the journalist's questions by implying Paul is racially motivated to keep African art out of the collection. What appears on the front page of the local paper is the word "racist." Paul protests to Sterling and demands an apology. Sterling refuses and soon a bitter legal battle commences in which both sides act foolishly. Sterling seems to be motivated by an entrenched inferiority complex and makes the mistake of screaming the word "Fuck" into Paul's face. Although he is from a corporate world, he apparently has never had to deal with the words "hostile work environment." Very much like Alfred Morris himself, North desires to maintain an autocratic rule, and is willing to take the Foundation into court on several fronts to create his own vision. For his part, Paul comes across as one of the pretentious art insiders that Alfred Morris despised,. In addition, Burrows continues to speak with reporter Gillian Crane to the point where he jeopardizes Kanika's working relationship with Sterling.

Is race an issue? Yes -- on both sides. Paul is, unknowingly, racist and rude. Not only in his comments to Sterling but in his estimation that African art is less worthy than a Matisse or Cézanne. Which, of course, is like comparing apples and oranges to decide which is the better fruit. They each have their contribution to the food group. Meanwhile, Sterling is consciously distrustful of whites and interprets every statement and action as potentially racist. Where Paul is completely unaware, Sterling is hyper-aware. They end up looking like children fighting on a playground. Thus the battle itself is really secondary to the questions which are raised -- is the art world color blind or blinded by color?

Permanent Collection is inspired by the Barnes Foundation located outside Philadelphia, PA whose eccentric founder, Alfred Barnes, was a difficult, opinionated idealist. Mr. Barnes created exhibits that showed the connectivity between different artists and art styles. Thus he grouped paintings to show how the artists inspired and played off of one another's creations. In a Barnes' exhibit a Modigliani would be beside an African sculpture, because Barnes felt that the artist had been inspired by African work, as shown in his use of lengthened, extended necks. Mr. Barnes, though, never intended his foundation to be a museum; it was specifically a school for the common man. No tuition, no prerequisites, just a desire to learn. Having an Ivy League education background could be detrimental as Alfred Barnes would refuse people admittance on his own whims. T.S. Eliot's request was denied, as was millionaire art collector Walter Chrysler, Jr.'s. When he died, Alfred Barnes bequeathed controlling interest of the Foundation's board of directors to Girard Trust Bank and Lincoln University, a small historically African American institution.

Director David Schweizer has brought together a terrific cast. The battles between Sterling (played by Terry Alexander) and Paul (played by Thomas M. Hammond) are at times so vicious that it's no wonder the two men shake hands at the curtain call. The piece's timing is near perfect and the omnipresent, yet never intruding, specter of Alfred Morris (played by John Ramsey) is done exceedingly well.

Andrew Lieberman's scenic design is a unique changeable space, where at times the audience are viewers of the art and at other times the art being viewed. Picture frames move up and down, exhibit pieces change, a faux Greek-like panel reveals a scaffold which becomes an apt perch for Alfred Morris to watch over his beloved collection.

Within the cast, Terry Alexander portrays a likeable and polished Sterling North. As the play progresses, Mr. Alexander slowly dulls the luster as more of Sterling's own inner insecurities emerge and you realize the lengths he will go for self-validation. Thomas Hammond's Paul is alternately jovial and condescending. You see why he would be engaging as an art lecturer and also why he is a divorced workaholic.

As the ghost of Alfred Morris, John Ramsey gives the air of cantankerous glee and demanding ego solely by his monologues and physical expressions. The youthful "next generation" is represented by Quincy Tyler Bernstine as Kanika Weaver. She makes the most astute comments about the situation when she remarks "Neither of you listen to each other." and then asks Paul why she can't be comfortable within herself, like he is within himself. A comfortableness, she says, that is derived from seeing yourself reflected in the world around you. And she follows this up with a look at the fear that both whites and blacks have of each other and longs for the day when that fear will vanish.

Elain R. Graham's Ella is at first the efficient executive assistant and then a woman who comes into her own as a result of the legal battle. She flows between the roles quite well. And as Gillian Crane, Christina Rouner offers an unsympathetic portrait of a reporter trying to be fair, yet at the same time a part of the community around her. Trying to get people to talk and then reporting their words is her job. Catching them in a moment of ill-thought comment is simply part of the territory.

While Permanent Collection comes across as slightly more about male egos, its examination of race will stir up discussion on all sides: black, white, male, female. Its greater purpose may be to ask: Why is some art relegated to the storage bin and other art on permanent display? Who has decided what is the "the best" and what criteria is being used. The National Museum of Women in the Arts has a wonderful collection by the way...

|

Permanent Collection by Thomas Gibbons Directed by David Schweizer with Terry Alexander, Quincy Tyler Bernstine, Elain R. Graham, Thomas M. Hammond, John Ramsey, Christina Rouner Scenic Design: Andrew Lieberman Costume Design: Michael Krass Lighting Design: Matthew Frey Sound Design: Vincent Olivieri Running Time: 2 hours with 1 intermission Centerstage, 700 North Calvert Street, Baltimore Telephone: 410-332-0033 TUE - SAT @8, SAT - SUN @2, SUN @7:30; $10 - $60 Opening 03/11/05, closing 04/10/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 03/16/05 performance |

Easy-on-the budget super gift for yourself and your musical loving friends. Tons of gorgeous pictures.

Retold by Tina Packer of Shakespeare & Co.

Click image to buy.

Our Review

At This Theater

Leonard Maltin's 2005 Movie Guide

Ridiculous!The Theatrical Life & Times of Charles Ludlam

6, 500 Comparative Phrases including 800 Shakespearean Metaphors by CurtainUp's editor.

Click image to buy.

Go here for details and larger image.